The Wonderfall at Changi International Airport, Singapore

Office Reorganization

Last year we reorganized where I work. Here are a few pictures of the results.

Welcome

To mark my 2019 birthday, I’m starting a new blog and dedicating the first post—a response to Richard Thompson’s 2018 album, 13 Rivers—to my friends at KTUH-FM.

When I was a UHM student, I volunteered for the station. Fred Barbaria was the general manager, and my teammates included Mike Holland, Russ Roberts, Ross Stephenson, and Rick Lenox. As I recall, I typed the program guide on an IBM Selectric and ran off copies on a Gestetner machine. Thinking back on those days, I’m filled with great affection for the people and great embarrassment at my terrible work habits.

Last year, I had the chance to appear on KTUH in connection with Ms. Aligned 2: Women Writing About Men. Along with Angela Nishimoto and Mary Archer, I read my writing and answered questions posed by Anjoli Roy, the host of It’s Lit with PhDJ. I am grateful to Anjoli for helping me renew my connection to KTUH.

Richard Thompson’s 2018 album

I don’t know how the creative process works. I suppose it is some kind of bizarre parallel existence to my own life. I often look at a finished song and wonder what the hell is going on inside me. We sequenced the weird stuff at the front of the record, and the tracks to grind your soul into submission at the back.—Richard Thompson

The cover of the 13 Rivers CD jacket has a color photograph of Richard Thompson sitting at a large black table. Several framed pictures—a few with gilt edges—hang on the dark wall behind him, and below them is a charcoal-gray credenza. The depth of field is shallow so that the background and foreground are blurred but Thompson is in sharp focus. He wears his trademark beret and a black leather jacket. His narrow face comes to a point with his neatly trimmed white beard, and his hands are clasped. A smile plays about his face, and the look in his blue eyes is kind.

Inside the CD jacket is a painting by him. At the center is a wide lake from which radiate curved lines, and along these lines are handwritten the titles of the album’s songs. Mountains and forests are part of the landscape and are given their own names. For example, the song title “Do All These Tears Belong to You?” is placed next to the heart-shaped grove named Silva Amoris (“forest of love”). In comparison to the hard-driving music of most of the album, the painting is light and fresh, suggesting a quiet, benign place of creation.

Released in 2018, when he was sixty-nine, the album features thirteen Thompson compositions. In these songs, he draws from idioms as diverse as hard rock, folk, blues, and the traditional music of Britain, including its bardic storytelling, and displays his signature guitar work, backed by drummer Michael Jerome and bassist Taras Prodaniuk. Bobby Eichorn joins them on guitar, and harmony vocals are provided by Siobhan Meyer Kennedy, Judith Owens, and Zara Phillips.

The most disquieting song on 13 Rivers has to be “The Dog in You.” Rather than seeking love and fulfillment as most of us do, the “you” seeks out “the innocent, the frail” in order to hurt and exploit them. It’s tempting to think the song is about a particular individual, but many people could fit the description of a sociopath who gets pleasure, “a twinkle in [the] eye,” out of someone else’s suffering. This disturbing portrait is heightened by the slow, bluesy tempo and the sardonic twist Thompson gives the word twinkle when he utters it.

In contrast to “The Dog” are several songs in which there are spiritual or existential questions for “you.” For example, “The Rattle Within” mentions a voice that could be that of a modern conscience, something that rattles us as we go about our daily business. The imagined “you” is “fixing to win” when he experiences “that wondering deep inside.”

That voice might come when you’re taking your pleasure

That voice might come when you’re resting your bones

It’ll seek you out when you’re sad or smiling

It’ll track you down when you think you’re alone

In “My Rock, My Rope,” Thompson gives this voice a more personal quality, letting it express a desire for spiritual emancipation.

O let me be uplifted

O take this weight from me

And heal me from my demons

And forever I’ll be free.

Given the album as a whole, I don’t think these spiritual elements should be interpreted as a search for religious comfort but for a deeper, more genuine existence.

As Thompson describes it in “Her Love Was Meant for Me,” loving is also a struggle for realness and authenticity. The speaker warns a rival to “put your eyes back in their sockets / keep your paws off the upholstery / put your hands back in their pockets.” The odd placement of sockets, upholstery, and pockets in the stanza of a love song comes after lyrics that are almost courtly:

Gypsy finger traced my loveline

She’s my soul and destiny

Three times I turned the queen of hearts

Her love was meant for me.

With a hard-driving melody, bass, and drums—and closing notes that instead of fading build to a crescendo—the song asserts the rightness of a lover and the wrongness of whatever opposes him.

The questioning in the album’s last song, “Shaking the Gates,” is a surprise:

If angels are real, then who needs dreams?

Think I’ll never close my eyes again

If my feet betray me, lock the door

My heart may never be this wise again

I’m shaking the gates of heaven

The fate of the “I” is open-ended, and the voice is gentle, rueful, and accepting. The sadness here links to the resignation in the album’s opening song, “The Storm Won’t Come,” in which the speaker yearns for a purifying form of destruction:

I'm longing for a storm to blow through town

And blow these sad old buildings down

Fire to burn what fire may

And rain to wash it all away…

There's a smell of death where I lay my head

So I'll go to the storm instead

I'll seek it out, stand in the rain

Thunder and lightning, and I'll scream my name

The storm is, of course, a metaphor for events that alter a person’s life, and the music evokes not only a storm’s violence but also its potential for re-creation.

Still vigorous and innovative, Thompson continues to generate excitement when he releases new work. With the tremendous energies of Jerome and Prodaniuk added to his, the engine of his music is masterfully constructed.

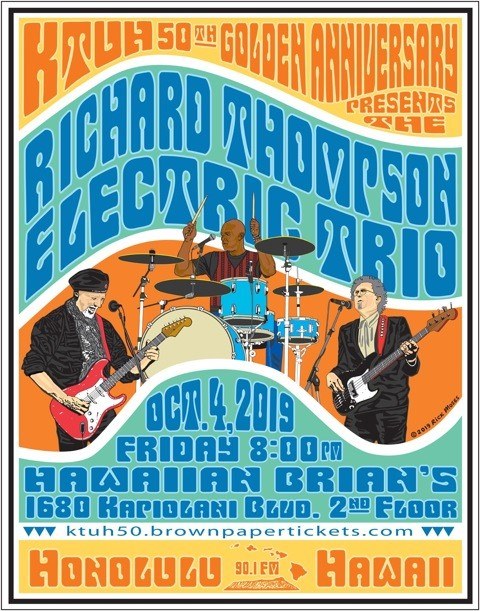

Thompson’s seventieth birthday will be celebrated at a special event in September at Royal Albert Hall. Shortly after, he will be in Hawai‘i to help KTUH-FM, the University of Hawai‘i’s student-run radio station, mark its fiftieth birthday.

Photo of Richard Thompson from Unhalfbricking, Fairport Convention’s 1969 album.

Links

Wikipedia biography and discography.

Website discography.

Website photos and videos.

Solitary Life, a seven-part BBC documentary. This takes a little less than an hour to view and is well worth it if you want to learn about Thompson’s family, early years, and personal life. In addition, fellow musicians, critics, and industry insiders share their insights about his personality and career.

Michael Jerome, drummer.

Taras Prodaniuk, bassist.

Linda Thompson, singer once married to Thompson.

Sandy Denny, lead singer of the Fairport Convention and composer of “Who Knows Where the Time Goes.”